Mosaic: evidence of eras, religions and cultures in the Holy Land

Introduction

The mosaic constitutes, thanks to its great antiquity, a unique piece heritage in mediterranean art and culture. In particular, the cradle of most antique civilization and crossroads of histories and populations, conserves today the history of this greatly rich and diverse patrimony. The mosaic is a testimony of the epochs, of the religions and of the cultures which have been encountered and are still encountered today, representing at the same time a common medium through which they dialogue and have dialogued in the course of history.

This mediation function of the mosaic art in this region, today represents also an important opportunity for intercultural dialogue, combatting stereotypes, promoting the cooperation and the sharing of common values internal to the whole of the mediterranean. Common actions, in fact, have been undertaken by artists and conservators to preserve and keep alive the tradition of this art and, sometimes, to make it an element capable of driving social and cultural development actions (we mention for example the work carried out in recent years by the Mosaic Center in Jericho).

The history of mosaics

The production of mosaic designs is one of the forms of the most antique forms of art in human history. It was born as an art essentially tied to architecture. Composed of stone or stone-like elements of smal dimensions lying on a bed of mortar, it is integrated with other structural elements like walls and pavements, forming paintings or decorative motifs. The original scope of the mosac was purely functional, but with the evolution of this art and the progress of this technique, it also a acquired a decorative function.

The knowledge and the practices of this form of art were born in Mesopotamia, where the history of the mosaic emerged nearly 3000 years ago, when tiny fired clay cones were used for the first time as a durable cladding for the walls of raw brick structures. The bases of these cones were sometimes colored with black, white, or red, and a pattern was obtained when the small ends were inserted into the damp mud plaster used to cover the walls. This was the first form of the mosaic that has been discovered to date.

The Minoan-Mycenean civilization, in the course of the 2nd millenium BC, began to use a pavement of river pebbles, in order to give a greater durability and to make the floor waterproof. The same type of pavement from mosaic, with figural representations, is found in various city centers in Greece, dating from the 5th – 4th centuries BC. The transition to tessellation, that is to mosaics composed of tesserae, in the 3rd c. BC, is documented in various regions of the Hellenistic world without the need to recognize a single center as the engine.

The mosaic in the Roman era undertook a different development with repect to the Greek tradition. The decorative apparatus would be more diverse, from themes figurative and mythological to those geometric and vegetable. The mosaic remained a luxury good, and therefore used almost exclusively in noble villas and palaces, until the second half of the 2nd century B.C. when the bichrome mosaic (black and white) widely used in spas, public areas, and even in homes became widespread, combining simplicity and economy with a very wide range of possible variations.

This ancient mosaic technique, consolidated in Roman and then Byzantine times, together with floral and geometric designs and motifs, was absorbed by Islamic culture in the East: the first Muslims preserved and transformed this art form – the same word in Arabic for mosaic, fuseefasa, is derived from the Greek psifosis.

In the sacred places of Islam the mosaic is found on the walls, the floor being a space dedicated to prayer. Byzantine reminiscences are found in the floral motifs on a golden background inside the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and in the Umayyad mosque in Damascus.

But above all, geometric motifs would be the true protagonists of Islamic art. They would develop mosaic design and technique and then give life to new forms of tessellation such as zellige, girih tiles and shakaba stained glass, widely used in architecture.

The mosaic would also be the element privileged by the Italian artists and architects who worked in the Holy Land since the 1920s, guaranteeing a certain artistic and stylistic continuity to the holy places with respect to their history. Barluzzi, Villani, D’Achiardi are some of the artists who used mosaics in decorating restored or newly constructed sanctuaries, leaving modern interpretations of this ancient and immortal art.

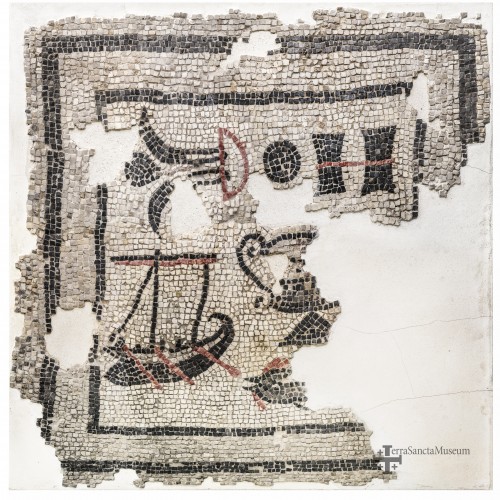

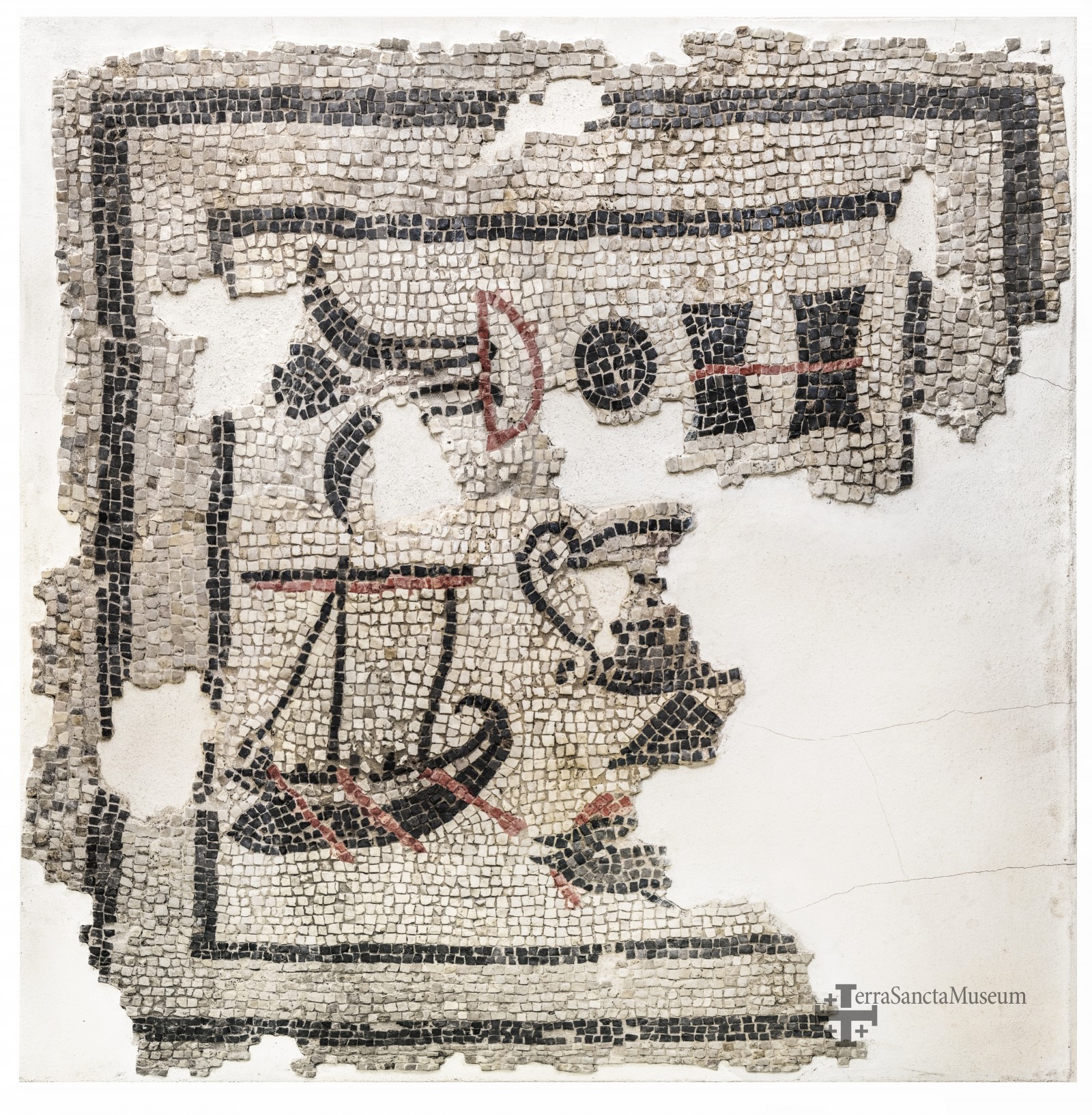

Mosaic with Boat, Magdala, 1st century

This fragment of a mosaic, now preserved beneath a panel, belonged to a small room, completely covered with mosaic, inside a thermal building located on the shores of the sea of Galilee. At the time of discovery, the figurative frame was placed in the center of the compartment, while on the edge there was the Greek mosaic inscription “KAI CY” (“You too”), a formula that traditionally aimed to prevent the effects of the evil eye.

The decorative apparatus consists of a ship, a dolphin, a drinking cup (kantharos) a ring, from which are hung two strigils (a metal instrument used in antiquity, at the spa or in the gym, to cleanse the mixture of oil and dust used to clean the body) and a jar for ointments (aryballos), a disc and a pair of dumbbells for attics (haltares).

Overall, the scene seems to refer to an environment of well-being and prosperity, linked to the various activities practiced in the baths, where water is constantly present: body care was accompanied by long conversations sometimes combined with the pleasures of wine and food.

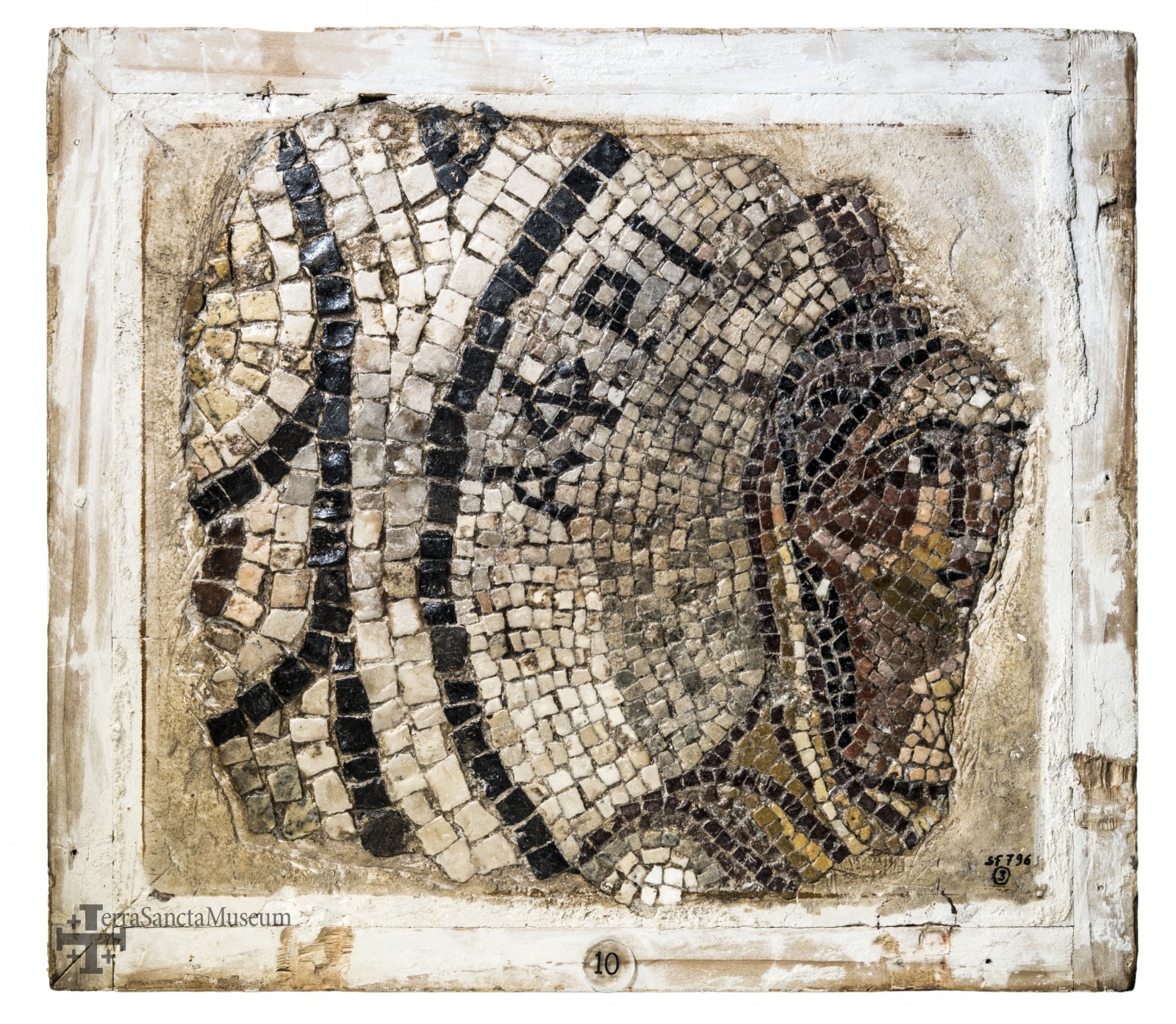

Mosac with personification of the province, 2nd –3rd century

The mosaic fragment of polychrome tesserae in limestone and marble, with a personification of the African province, originally belonged to the floor of a Roman villa in Belkis (today: Graziantep, Turkey), with an articulated decorative program, which included Poseidon on the chariot in the center of the scene and several personifications of other provinces (Germany, Mauretania, etc.). Africa is represented as a female figure with a halo, head veiled and crowned with a turreted crown; in the upper area there is an inscription with an abbreviated title in Greek capital letters, : ΑΦΡΙ, for Africa.

Constantinian Mosaic in the Basilica of the Nativity at Bethlehem, 4th century

The floor mosaics found inside the Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem are characterized by polychrome tesserae (white, black, red, ochre and grey) and for the most part by geometric decorative motifs.

The nave houses one of the largest fragments found, where we can see a central part with a decorative pattern of interlaced strips to form a circular motif and a band of contour consisting of acanthus girals.

Of particular interest are two panels very similar to each other, divided into six panels by a swastika, where in the upper middle one we can read an inscription in Greek letters: IXΘΥС i.e. Iesùs Christòs Theù Hyiòs Sotèr, “Jesus Christ Son of God the Saviour”.

In the aisles you can see other decorative motifs such as fish scales and geometric motifs and cruciform leaves.

According to studies carried out by Father Bagatti between the end of 1947 and 1952, this is the first pavement made in the Basilica because a direct contact of the layers of mosaic preparation with the natural rock was observed. They have recently undergone restoration work that has restored the mosaics to their former glory.

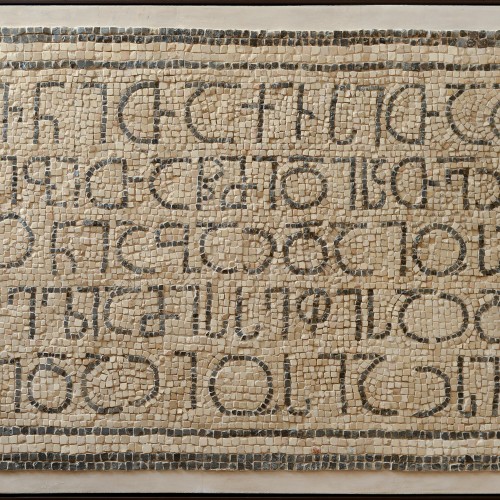

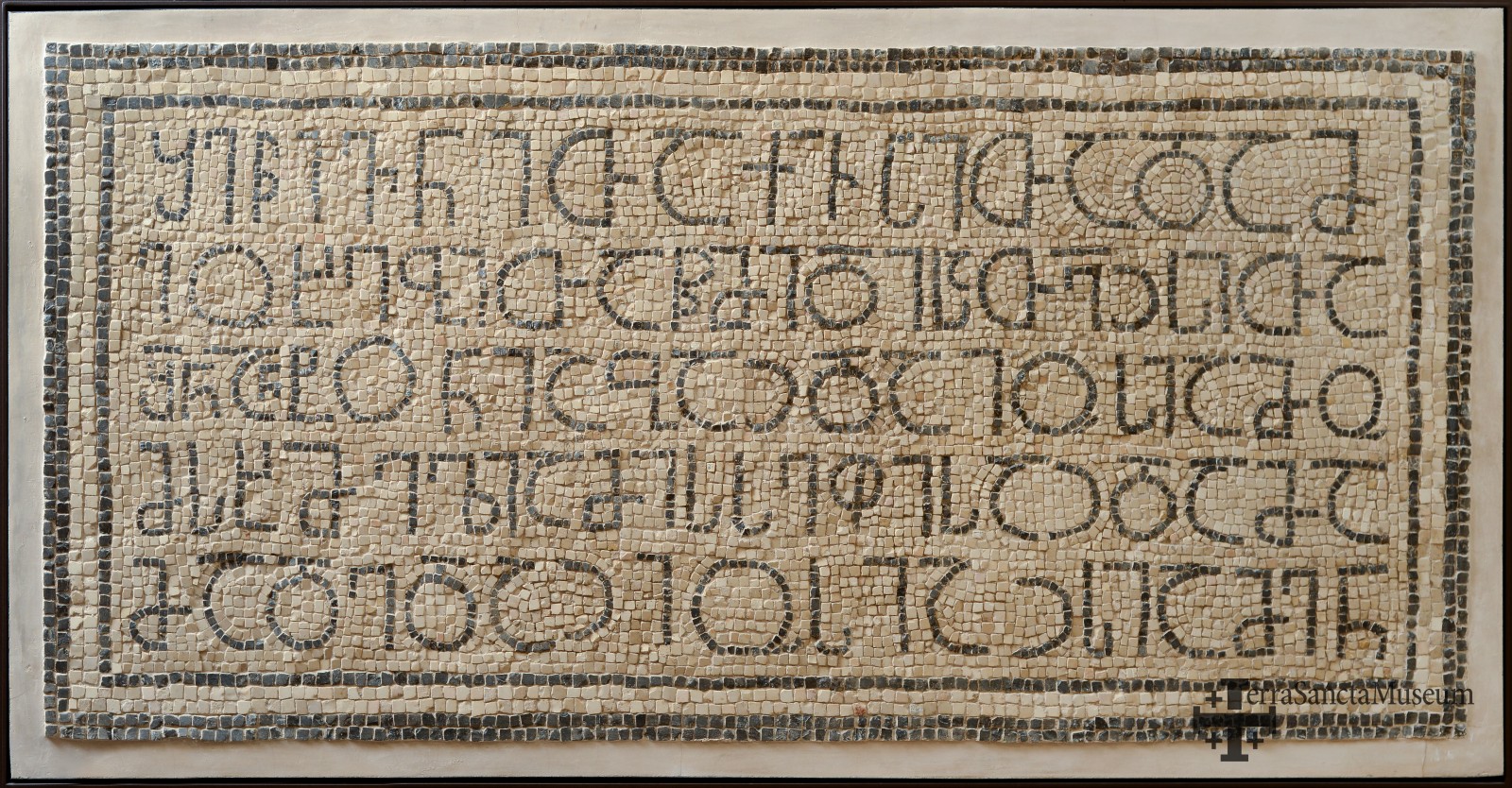

Mosaic with a Georgian epigraph in the Monastery of Bir el-Qutt, 6th century

It is a fragment of mosaic floor with black, white and beige tiles, the epigraphic text in Georgian language and characters is arranged on five lines and is inserted in a rectangular frame consisting of two black strips of different thickness alternating with a beige strip. The well arranged letters are made of black tiles. The lines are separated by a double-layer strip of beige tiles.

The Georgian inscription reads: “With the help of Christ and through the intercession of St. Theodore, God have mercy on Abba Antoninus and Josiah, the maker of this mosaic, and on Josiah’s father and mother”.

The epigraph and other mosaic floors with inscriptions found in the monastery of St. Theodore in Bir el-Qutt, represent some of the oldest evidence of the Georgian language in Palestine. It is worth remembering that the area around Bethlehem became a centre for monasticism of Iberian origin from the 5th century AD.

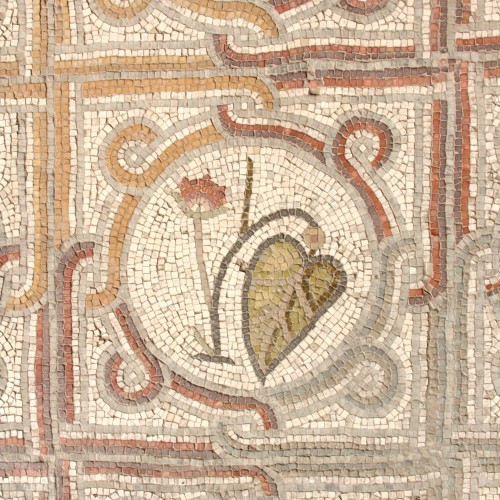

Mosaics of the Oratory, sanctuary Dominus Flevit, 7th century

The mosaic belonging to the oratory of Dominus Flevit consists mainly of polychrome tesserae of calcareous material. The central field is tripartite. The wider area is made up of an interlacement of strips with knotted circles loaded with various figurative decorative motifs. An iconography very dear to Christianity has been used since the 3rd and 4th centuries: parts of fish, whole fish, floral and vegetable motifs or even fruits such as pomegranate, figs, watermelon, apple, pear or cluster grapes, references to life and rebirth, symbols of the passion of Christ and his Ekklesia (mystical body).

Mosaics of Mount Nebo, 6th–7th century

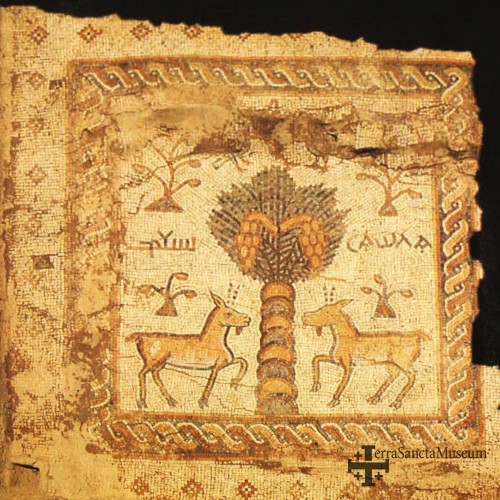

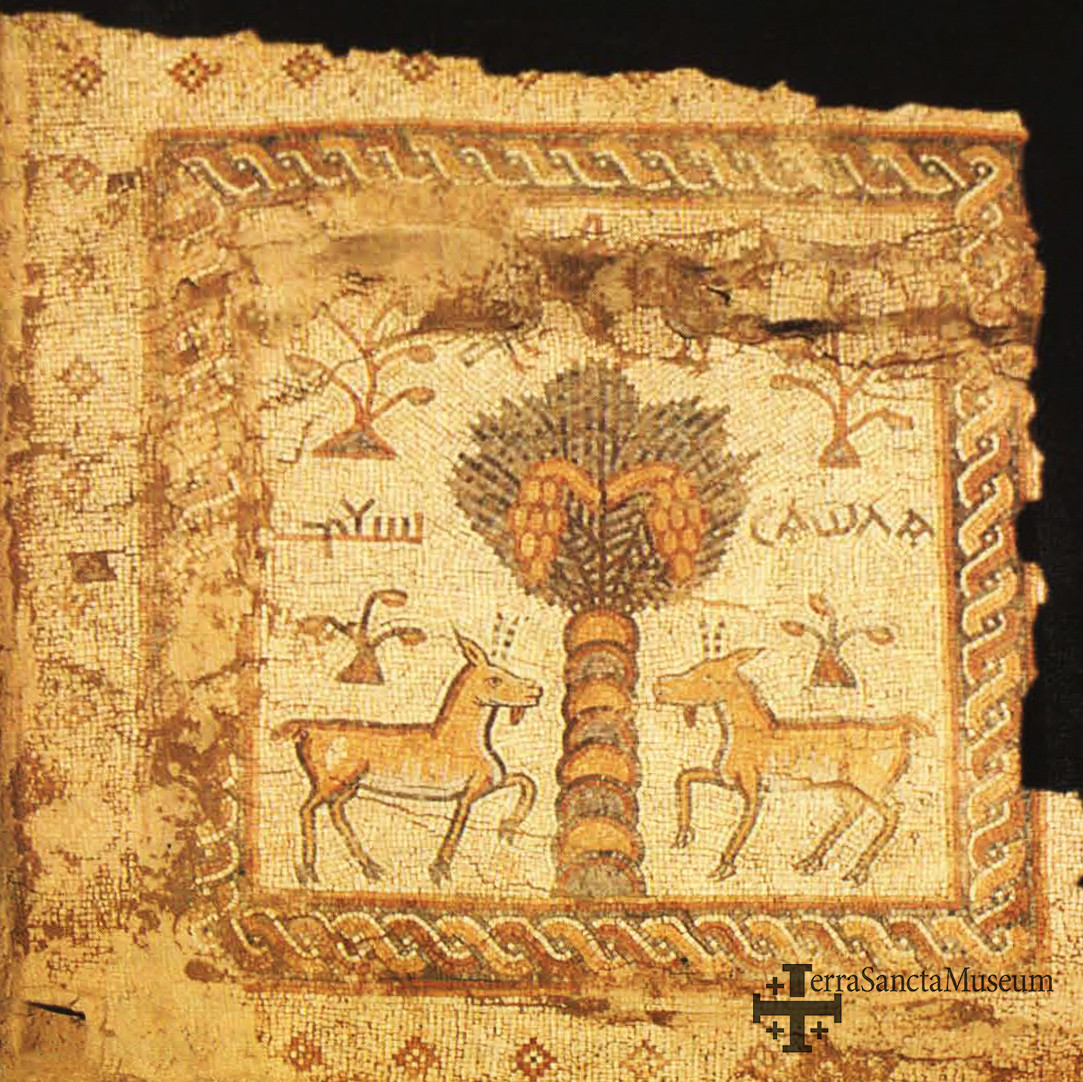

Two mosaics of particular interest come from Mount Nebo in Jordan.

Here in 1932 the Custody of the Holy Land purchased the area of the peaks of el-Mukhayyat and Siyagha, where excavations began the following year under the guidance of Fr. Saller and Fr. Bagatti of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum.

The primitive sanctuary of Siyagha dates back to the 4th century when a building from an earlier period was adapted to form a church. The Chapel of the Theotokos (Mother of God), an apsidal hall divided into two rooms, dates back to the 7th century. Here there is a rectangular mosaic with a representation of two gazelles next to two flowering bushes and two bulls facing a building. This building inspires interest because it is identified as a representation of the Temple of Jerusalem in which we can see the altar with flames above and the ciborium below with a table of propositions. All this is accompanied by the inscribed quotation of Psalm 50 which reads “Then they will sacrifice victims above your altar“.

Mosaics of Mount Nebo, VI-VII century

In the 6th and 7th centuries it was very common to adorn walls and floors of sacred places with mosaics (also called psifis or psifosis). Of these today only the floor mosaics and remain, as well as some inscriptions in Greek, the language known to the clergy and used by Byzantine administration. Of exceptional interest is the Semitic inscription of a single word, present on a mosaic in the chapel south of the apse in the church of St. George in Khirbat al-Mukhayyat. The inscription appears next to the name of Saola, one of the church’s benefactors. Some scholars also suggest that this inscription may be an Aramaic Christo-Palestinian inscription meaning “God from Saola” some others suggest that it recalls the Arabic expression “bisalam” and therefore may mean “In peace“. If the latter theory were correct, we would have the first attested inscription in Arabic written in a mosaic in Jordan.

Crusader-era wall mosaics of the Basilica of Bethlehem, 12th century

Not much remains of the mosaics made during the Crusade (12th century), victims of erosion and various historical events.

In the wall above the columns of the nave it is possible to observe a procession of angels in the upper part and the depictions of Jesus’ ancestors in the lower part. The middle part, on the other hand, represent the various ecumenical councils held in the East wherein each council is represented by an opulent church, along with the relevant canons drawn up in Greek.

In the transept we can see scenes from the life of Jesus represented, among which the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem and the Transfiguration, where the use of the Latin language is attested, testifying to how in that period the two confessions lived in a period of quiet collaboration.

The artisans who realized the mosaics were of Syriac origin ; their names remain in the decoration (Basilios and Ephrem).

Mosaic Mount Tabor, Villani, 1921

During the last century the restoration and reconstruction of the ancient sanctuaries by Italian architects and artists, especially by Antonio Barluzzi, took the whole historical tradition of mosaics in the Holy Land into consideration, very often interpreting the art of “psifosis” in a modern way.

The restoration of the Basilica of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor is the first work of Antonio Barluzzi in the Holy Land. The preparatory cartoons were designed in Rome and then created and translated into mosaics by the Vatican’s Monticelli company.

The iconography follows ancient tradition: the transfigured Christ is flanked by the prophets from above and the apostles Peter, John, and James below. The composition, clear and simple, is set against a golden background that manifests the epiphany of the divinity, to arouse admiration and devotion. The style is appropriate to the historicist taste of the time: it references Byzantine art even in the details of the palms and Christograms that border the mosaic.

Italian vault mosaic Gethsemani, D'Achiardi, 1927

Barluzzi directs the works of the Basilica of the Agony of Gethsemane, known as the Basilica of All Nations, located at the base of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. The architect asked the artist Pietro d’Achiardi (1879-1940) to decorate the twelve domes of the nave, whose structure was inspired by St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. Each dome, covered in mosaics, bears a star decoration on a blue background, embellished with decorative motifs and the emblem of the nation that financed the decoration.

The Italian dome stands out for the richness and refinement of its decoration. Four angels sit in the pendentives of the dome, on a blue background with golden volutes, seem to support the dome.

The decoration synthesizes several sources of inspiration, including the mosaics of the vault of the Sacello di San Zenone, inside the Basilica of Santa Prassede in Rome (one of the most precious examples of Byzantine art in Rome in the 9th century) and the early Christian vault of the baptistery in Ravenna (early 5th century).

Mosaics of the Latin Chapel in the Holy Sepulchre, 1933

In the 1930s, Barluzzi undertook the restoration of the Latin Chapel from Calvary to the Holy Sepulchre, just above Golgotha, on the site of the Crucifixion.

Pietro d’Achiardi assisted on the vault, setting up a decoration with a rich Christian meaning: the vine and the acanthus were chosen for their lightness and vivacity, but above all for their allegorical meaning, linked to the Resurrection and the Eucharist. Since the vault still contained a fragment of the original 12th century cross-shaped mosaic decoration, he decided to preserve it by integrating it into the new mosaic. The fragment, which represents the pantocrator Christ of the 12th century surrounded by an almond, and the decoration of golden vine leaves and acanthus on a blue background harmonize particularly well. The iconographic programme built around the fragment is clear and perfectly integrated with the original mosaic: it shows the salvation made possible by Christ’s sacrifice.

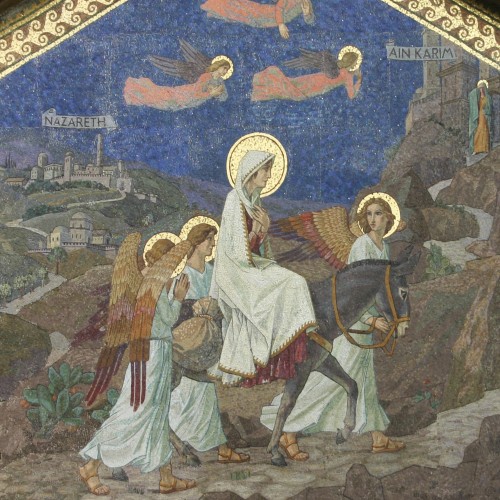

Mosaic facade Ain Karem, Biagetti, 1937

The mosaic, executed in 1937 according to the cartoons of Biagio Biagetti (1877–1948), welcomes the visitor from the entrance portico on which it was installed.

The Virgin, after the Annunciation in Nazareth, rides a donkey to Ain Karem to visit her pregnant cousin Elizabeth. Angels accompany her on this winding and mountainous path, and Elizabeth waits for her on her doorstep. In the lower part, under the golden frame, a quotation from the Gospel according to St. Luke (1:39-56) describes the scene.

Biagetti is stylistically inspired by the great Italian masters of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, in particular Fra Angelico (1395-1455), and above all by Giotto‘s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1305-1306). However, he adapted his work to the exhibition site, showing the local vegetation, which led the mosaic to be nicknamed “Madonna del fico d’india” (Madonna with prickly pear).