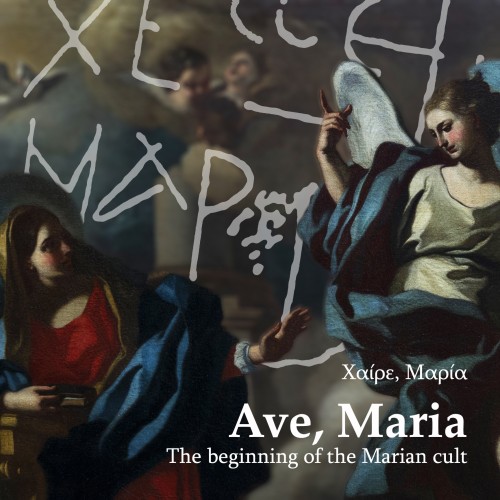

Χαίρε, Μαρία. Ave Maria. The origins of the Marian cult

The name of the city of Nazareth – which is cited neither in the works of Giuseppe Flavio, nor in Talmud – appeared for the first time in the Gospels.

According to saint Luke, the episode of the Announciation took place here during the sixth month of Elizabeth’s pregnancy. God sent the Angel Gabriel to Nazareth, a town in Galilee, to a virgin pledged to be married to a man named Joseph, a descendant of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. The Angel went to her and said: “Greeting, you who are highly favored! The Lord is with you.” Mary was greatly troubled at his words and wondered what kind of greeting this might be. But the Angel said to her “Do not be afraid, Mary; You have found favour with God. You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus”.

Over the centuries in Nazareth – specifically in the area where the Basilica is currently situated – various religious buildings have been built in order to honour the memory of the Announciation, but their history is often controversial. The excavations carried out by the Franciscans of the Studium Biblicum Francescanum, led by Father Bagatti in the 60s, represent a very important moment for the rediscovery of the origins of this sacred place of the cult of Mary in Nazareth.

This short multimedia exhibition presents the essential moments and details of that excavation.

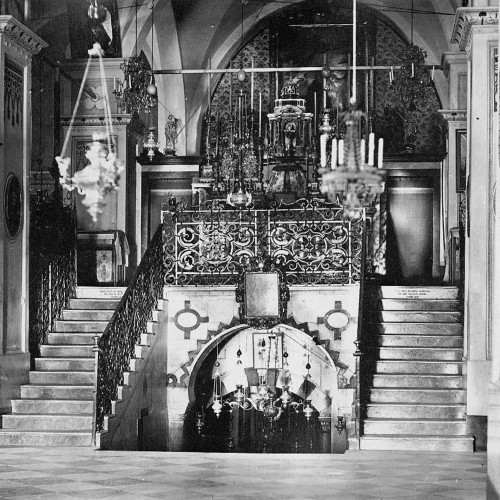

Church, xenodochius and Monastery of the Annunciation, Nazareth, 1882

Since the remote beginnings of Christianity, the city of Nazareth has been universally recognized as the city where, according to the Gospels, the episode of the Annunciation took place and as the place where Jesus lived. For obvious reasons, for centuries it has welcomed pilgrims and believers.

Picture from Album Missionis Terrae Sanctae, Jerusalem, 1882

The archaeological excavations carried out in Nazareth in the 1960s

Where does the story end and the cult begin? It is always very difficult, in the Holy Land, to identify and reconstruct exactly the history of the sacred places of Christianity. Often, however, it was thanks to the brilliant intuitions of the Franciscan friars during archaeological excavations that it was possible to reconstruct the history of a cult. This is the case with the Marian cult in Nazareth.

Picture from: Picture from Album Missionis Terrae Sanctae, Jerusalem, 1882

Interior of the Basilica of the Annunciation (about 1882)

For centuries in Nazareth, in order to honor the memory of the Annunciation, various religious buildings were built in the area where the Basilica is currently located.

Picture from Album Missionis Terrae Sanctae, Jerusalem, 1882

Father Bagatti and the excavations of Nazareth

It was in 1960 when, during the excavations in Nazareth directed by the archaeologist Father Bellarmino Bagatti of the Studium Biblicum Francescanum, several architectural finds were brought to light that were part of a monumental building that had preceded the construction of the first Byzantine basilica. It is a synagogue-church dating back to the second half of the second century, built around what according to tradition was identified as the house of Mary.

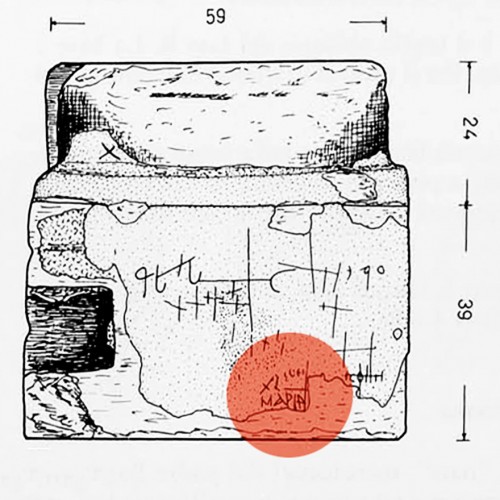

The detail on the base of the column

Among the findings, there is a column base engraved on the white plaster with graffiti left by ancient pilgrims. These are some names in Armenian and Georgian, superimposed on each other. But what catches the attention of archaeologists is an inscription in Greek.

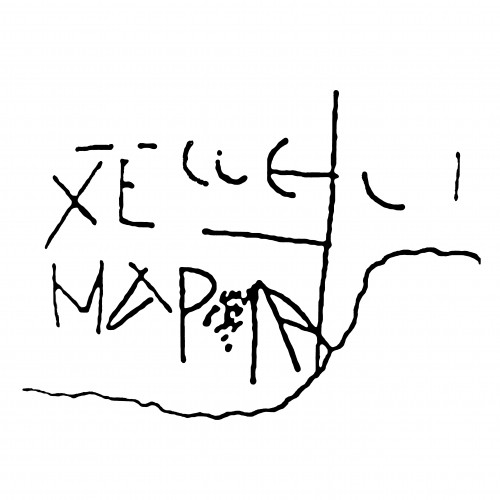

The engraving of Χαίρε, Μαρία

The engraving clearly shows the name of Μαρία “Mary” preceded by an abbreviation of two letters Χε , interpreted as Χαίρε “Chaire”, corresponding to the Latin “Ave”, that is the angelic greeting addressed to the Virgin, according to the Gospel of Luke.

This very small but important detail is immediately of great interest for the history of the Nazareth sanctuary.

It represents a testimony of the Marian cult prior to the middle of the fifth century AD, preceding even the Council of Ephesus, which represents the official beginning of the cult of Mary Theotokos, Mother of God. Thanks to its position, it will later allow Father Eugenio Alliata to put forward reconstructive hypotheses of the architectural layout of the ancient building that stood right around the Grotto of the Annunciation.

Details of the column base outline

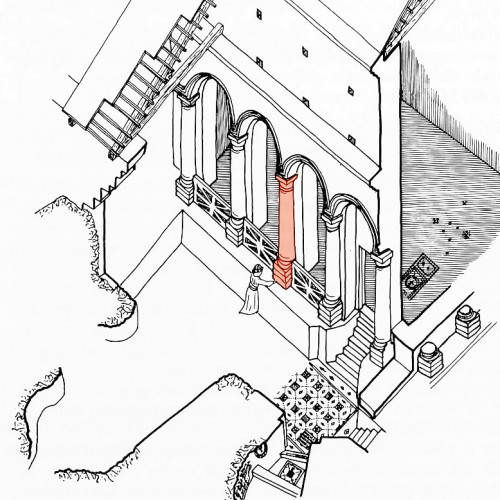

Observing well the shape of the base and the part of the “cheek” base of the column, Father Bagatti realized that since the columns were only finished on three sides, they had been prepared to be placed against some wall. The presence of the lateral staircases also suggests that there were barriers between one column and another.

Picture from: Liber Annus XXXVII, Studium Biblicum Francescanum, Jerusalem, 1987

Reconstructive hypothesis

But that’s not all: Father Bagatti’s hypothesis reconsiders the position of the columns, placing them about a meter above the ground, such a height that pilgrims would have been able to nimbly carve into the stone. This is why, most likely, the bases of the columns were in turn resting on a rocky bank, forming a portico or colonnade.

This colonnade would therefore have been part of a “noble façade” that gave onto the venerated caves.

Picture from: Liber Annus XXXVII, Studium Biblicum Francescanum, Jerusalem, 1987

The interior of the Basilica of the Annunciation today

The buildings on this sacred site have been demolished and rebuilt several times over the centuries. In the middle of the 4th century, during the Byzantine era, the synagogue-church was replaced by a more majestic building, probably commissioned by the Empress Helena. Another larger church was built in the 12th century by Tancredi Prince of Galilee, rebuilt after an earthquake in 1170 and then destroyed again in 1263 by the Mamluk Sultan Baybars. The Sultan spared the cave, which remained a place of pilgrimage and worship. In 1730 the Franciscans obtained permission to build a modest church, and finally in 1969 the contemporary Basilica was consecrated: the church, designed by Giovanni Muzio, preserves the memory of this sacred place, the origins of Marian worship, and, integrating the remains of the ancient churches into its architectural structure, preserves its history.

Bibliographical references

Album Missionis Terrae Sanctae: album Palestino-Seraphicum. SS. Locorum prospectum, religiosa domicilia, elementares pro utroque sexu scholas, alique opera Seraphicae Terrae Sancate Custodiae referens, Jerusalem, 1882;

Liber Annus XXXVII, Studium Biblicum Francescanum, Jerusalem, 1987;

B. Bagatti, Gli scavi di Nazareth vol.1 Dalle origini al secolo XVII, Collectio Maior 17, Jerusalem, 1967;

B. Antonucci, I lavori a Nazareth, in “Terra Santa”, Jerusalem, 1966;

L. Di Giannicola, La Terra Santa. Guida manuale del pellegrino in Terra Santa, Rome, 2000;