Liturgical Vestments Full of Meaning

Chasuble, cope, dalmatic… it can be difficult to find your way around the dressing room of officiants! Explanations starting from the collection of the Terra Sancta Museum in Jerusalem.

To veil and to reveal. This is the nature of Catholic liturgical vestments. Forming a collection of pieces united by a common material, colour or pattern, the function of these vestments is to clothe celebrants during religious ceremonies and to distinguish their role. The liturgical vestments change depending on the position as bishop, priest, deacon or subdeacon. Vestments are also known as liturgical ornaments, from the Latin ornamentum, which means “decoration,” and ornare, which means “to decorate,” or “to adorn.” The care given to the tailoring and embellishment of vestments, which is in itself a fine art, adds to the magnificence of the liturgy and encourages the faithful to turn towards the source of True Beauty, who is God. Although today’s liturgical vestments tend to be simpler and less ornate, the Church nevertheless recognises the importance of sacred art. The Second Vatican Council document, Sacrosanctum Concilium (1962), affirms sacred art as the human activity which is most predisposed to bringing us closer to the perfection of God.

Since their arrival in the Holy Land in the 13th century, the Franciscans have given the arts an important role in serving the liturgy. As Guardians of the Holy Places, the Franciscans have been receiving gifts from European royal courts since the Middle Ages, gifts that include lavish liturgical objects and vestments. This unique collection of 900 liturgical vestments will be exhibited in part in the future historical section of the Custody’s museum on the Holy Land, the Terra Sancta Museum. As we await the opening of the museum, let us begin by delving into the rich history of form and symbolism behind these liturgical vestments.

A Form of Greco-Roman Origin

The form, or shape, of liturgical vestments as we know them today has greatly evolved over the years. It originates principally in the Greco-Roman vestments worn by civilians in the 1st century AD. Under the Roman Empire, priests wore the same outfits as civilians, although they tended to be sewn from material of a higher quality. Over time the shape of priestly vestments was simplified, mainly for purposes of convenience and mobility, though the material and the complexity of their decor was given more importance, sometimes making the vestments quite heavy.

The chasuble, which is arguably the priest’s most characteristic vestment, takes its shape from the Roman casula, a large, broad mantel that would be donned by pulling over the head. The shape of the chasuble later evolved to be more rectangular in the back and pear-shaped in the front, leaving the arms and hands free. This shape eventually stabilised at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The cope (or pluvial) is worn by the priest or bishop for solemn functions, most notably during processions. From the Latin word cappa, meaning “hood” or “cape,” the shape is derived from the large overcoats worn by Romans to protect themselves from the rain. Semi-circular in shape, the cope envelopes the priest all the way to his feet, and is fastened around the neck by a clasp.

The dalmatic, whose name points to its Dalmatian origin, has been considered the quintessential vestment of the diaconate since the 9th century. It consists of a tunic with large sleeves that form a cross, introduced to the liturgy in the 4th century. Originally white, it progressively evolved to match the colours of the other liturgical vestments.

One can find evidence of the earliest vestments worn by priests in certain mosaic artworks of the 6th-7th century, most notably in the mosaic artwork of St. Apollinaris in Ravenna. At that time, one could still easily confuse a priest with a Roman civilian. Beginning with the elaboration of religious symbolism in the Middle Ages, however, liturgical vestments were eventually endowed with a unique Catholic identity.

A Mediaeval Symbolism

During the Middle Ages, the institution of the Church in Rome was gradually established through the help of new laws. The Church unified and codified various rites according to the Roman model. As a result, the use of colours and materials was regulated for the production of liturgical vestments. Around the 13th century, the first textile mills and workshops were established. We know today that the Franciscan convent of Saint Saviour in Jerusalem was used as a textile workshop for the production of Franciscan habits and the restoration of liturgical ornaments.

At this time, the Church attached symbolic meaning to liturgical vestments. The chasuble symbolised charity, necessary for the priest to celebrate the Eucharist. The dalmatic was associated with benevolence, innocence and joy.

The stole, which is the long scarf worn around the neck of officiants, enjoys a particular status because it is not a garment in the proper sense of the word, but an insignia. The stole is an accessory that allows the function of the celebrant to be distinctly marked. It recalls the grave responsibility that weighs on the clergy, as well as the grace of Christ that accompanies them. Deacons wear the stole across their body, going from their left shoulder to their right side, symbolising their devotion to the service of the mass. Priests wear the stole on both shoulders, crossed in front of the chest, according to the liturgical reforms of Vatican II. Finally, bishops let the stole hang around their neck.

A Variety of Materials and Decorations

The materials used in the production of liturgical vestments are also codified, although the rules remain flexible and the symbolism subjective. The only strict regulation seems to be the dignity of the material. Thus, the use of silk and of wool were the most widespread for a long time because of their excellent quality as well as their affordability. Things became more complicated beginning in the 19th century with the development of material blends and artificial materials, and as a consequence more decrees were signed by the Sacred Congregation of Rites. Wool was forbidden in 1837, and the use of silk for the fabrication of chasubles began to be regulated in 1882. Today one finds many vestments which are less ornate and more comfortable, made of synthetic materials.

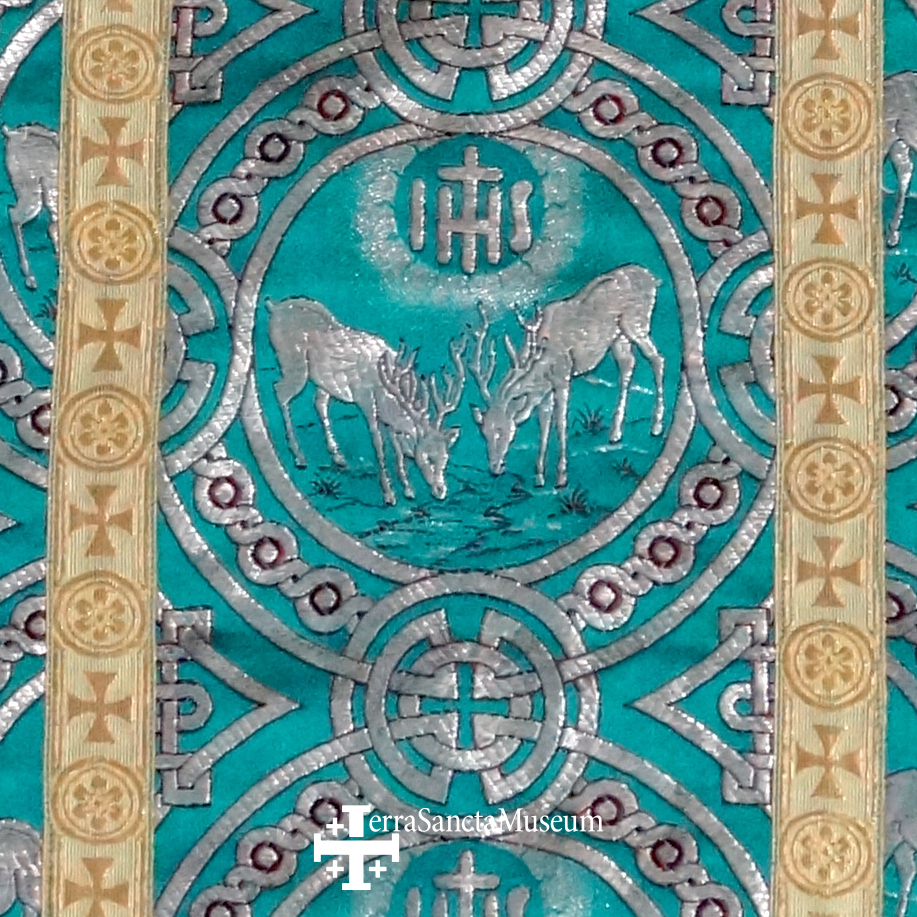

Decoration and adornment are certainly the most creative in the production of liturgical vestments as it is the least codified. Their role is both ornamental as well as functional, since they help to distinguish between the different liturgical vestments. They also work to reflect the symbolic focus of workshops and popular tastes. There is a wide array of methods for decorating vestments, to include fabric, painting, and embroidery. However, there is usually a background and braid trimmings, i.e. long bands embroidered with gold. The braids are used to outline the shape of the vestment and to make crosses. For those who take up the work of adorning vestments, embroidery is the most common mode of decoration. One finds representations of Biblical scenes in the Middle Ages, and in the 17th century, popular taste trended more towards floral patterns. From the 19th century, however, embroidery started to gradually disappear from vestments and was replaced by the use of rich, multicoloured fabrics.

Far from hiding appearances, liturgical vestments reveal the function of the celebrant and his role in the liturgy. Appreciable in their form, their symbolism, and their decoration, they mark the start of the celebration from the moment the priest puts them on. Thus officiants assume the role of intermediary between the faithful and God.

(Translated from French by Virginia Nyce)

Charles-Gaffiot, Jacques, Trésor du Saint-Sépulcre, Paris, Cerf, 2020.

Chatard, Aurore, « Les ornements liturgiques au XIXe siècle : origine, fabrication et commercialisation, l’exemple du diocèse de Moulins (Allier) », In Situ [En ligne], 2009. url : http://www4.culture.fr/patrimoines/patrimoine_monumental_et_archeologique/insitu/pdf/chatard-1325.pdf

Migne, Jacques Paul, Origine et raison de la liturgie catholique, Paris, coll « Bibliothèque universelle du clergé », (1844), 1863.