Some ruins of the Holy Sepulchre on display in the Terra Sancta Museum

A few weeks ago, a team of restorers led by Piero Coronas was in Jerusalem to prepare a curious operation: the moving of columns and capitals « from the Holy Sepulchre » to the Convent of the Flagellation, in the forthcoming Sylvester Saller wing of the archaeological section of the Terra Sancta Museum (TSM). What are these ruins and what is their history? Let’s look back at these unique pieces in our collections.

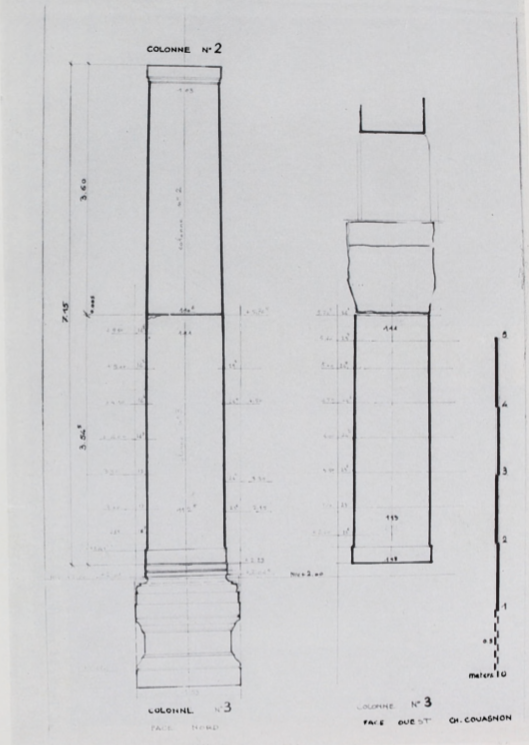

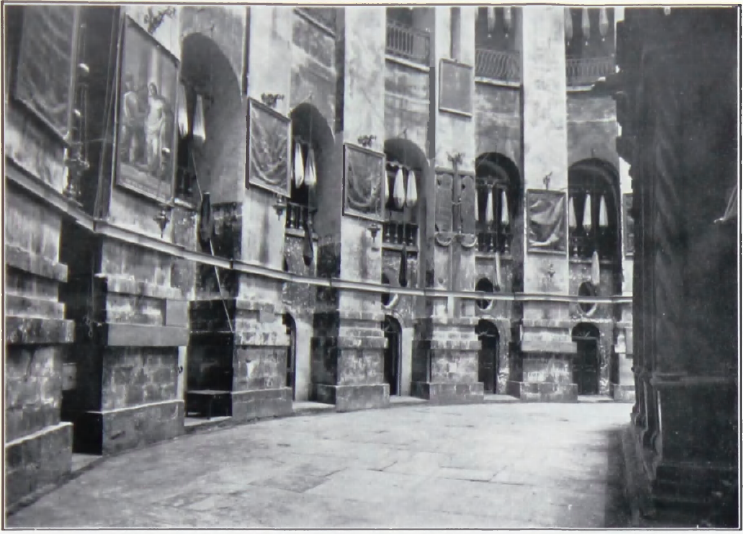

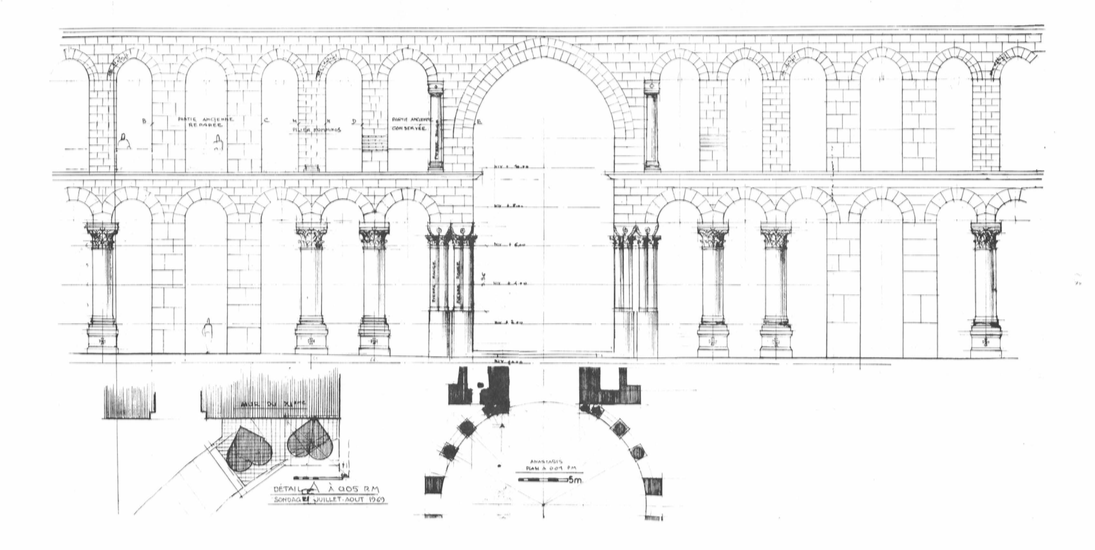

The story began in 1969 when major restoration work started in the Anatasis [1] of the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. In parallel with the dome, the works were also to restore the colonnade around Christ’s Tomb (fig. 1); the latter had been replaced by a wall under the British mandate (fig. 2), after the fires in the 19th century which had greatly fragilized the whole building.

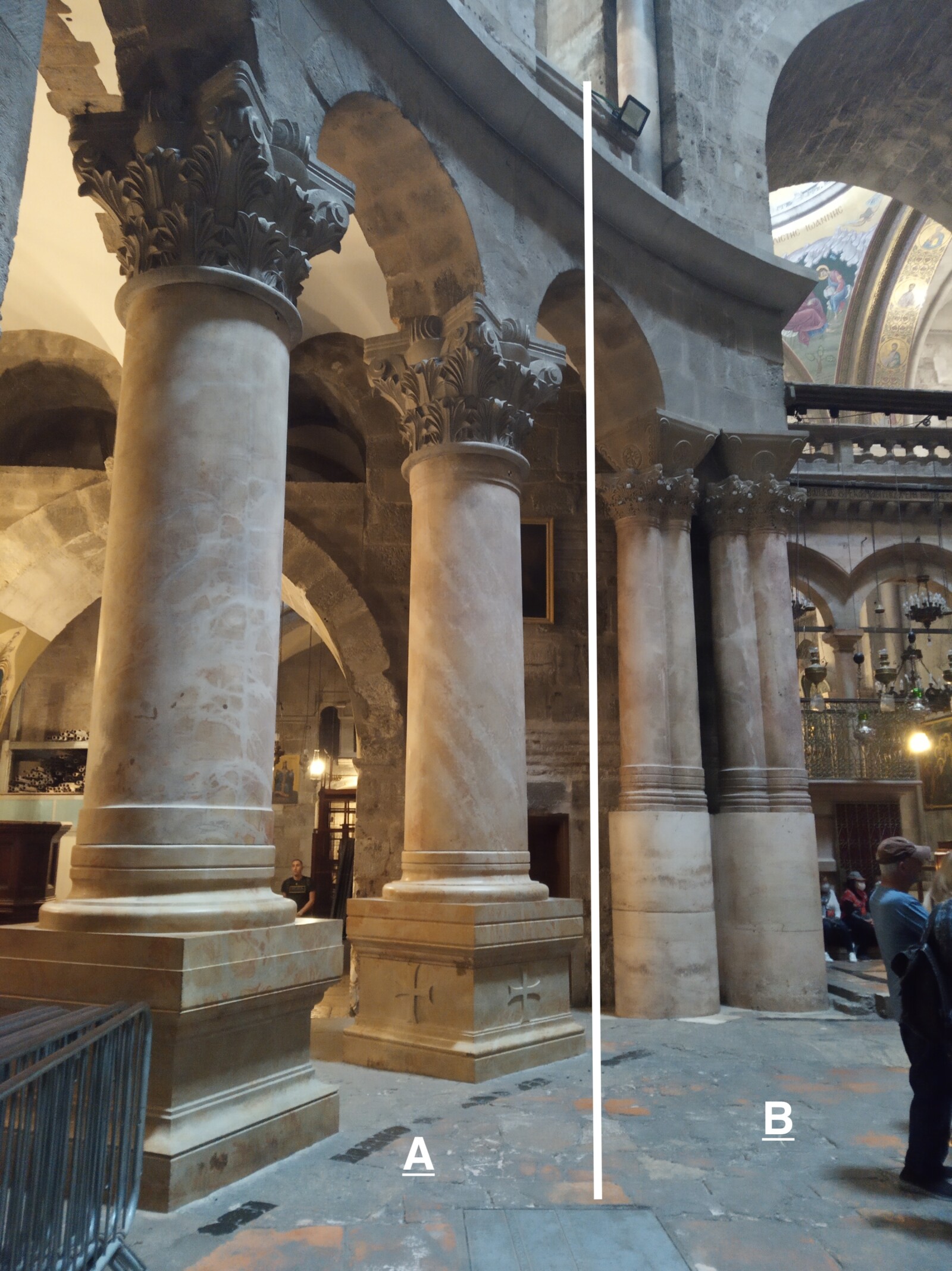

Inside the wall, two remains were discovered on the northern side (fig. 3, 4), in the part belonging to the Franciscans of the Holy Land. On the one hand, two monumental columns with Corinthian capitals [2], were part of the rotunda (below, « complex A »). On the other side, a couple of corner columns in the form of a heart, also with Corinthian capitals. The latter rested on a cylindrical block of marble and were surmounted by a second trapezoidal capital acting as an impost [3]. This second ensemble (below « complex B ») supports the arch of the entry to the Catholicon [4].

Very damaged, these pieces were removed from the church. Placed first of all on the esplanade of the entrance to the Basilica (fig. 5), they were finally moved to the hermitage of the shrine of Gethsemane (fig. 6, 7, 8).

Des colonnes romaines ?

The dating and the origin of the pieces are still uncertain. However, we can note a certain similarity between the pieces, apart from the pair of capitals used as an impost. According to Friar Virgilio Corbo, archaeologist of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, these ruins could have been placed there when the Holy Sepulchre was rebuilt by the Emperor Constantine Monomachos in the 11th century.

One of the hypotheses concerning the two columns of complex A attributes them to the reign of Hadrian (117-138). The emperor effectively ordered the reconstruction of Jerusalem during his reign and the building of a temple instead and on the place of Christ’s tomb [5]. Following the rebuilding of the church in the 11th century, the columns of this temple were alleged to have been reused to build a rotunda surrounding the Sepulchre. However, they are believed to have been cut into two: we can effectively observe that they could be placed on top of one another to form only one piece (fig. 9), one being wider than the other and showing a relief marking its base. Nevertheless, this hypothesis has recently been slightly modified by a team of archaeologists from Florence who explain that, according to the aesthetic canons of the Corinthian architectural order, one-third of the height of the original column is missing.

The story becomes even more complicated if we remember that many of the constructions of the reign of Hadrian re-used stones from the period of Herod (1st century BC – 1st century AD). “All the history of Jerusalem, all the suffering of this city and its destruction is contained in these columns,” comments Friar Eugenio Alliata, archaeologist and director of the archaeological section of the TSM. The debate on their origin is thus still open.

A same mystery surrounds the complex B supporting the arch of the entrance to the Catholicon, with the exception perhaps of the trapezoidal capitals. Several monograms in the name of the Byzantine emperor Maurice (582-602) and his family offer an important clue (fig. 10). No known work on the Holy Sepulchre was ordered by this emperor. On the other hand, the archives of the Georgian Church mention the dedication, by the same emperor, of a church near the Tomb of the Virgin Mary in Gethsemane, which was destroyed a long time ago. The hypothesis of reuse in the 11th century thus seems highly probable.

Whatever their origin, these ruins were used as a model for the contemporary reconstruction of the colonnade (fig. 11) surrounding the Tomb of Christ (still in place today). If it offers the advantage of a stylistic unity for the Anastasis, it is nevertheless true that this reconstruction is only based on these few specimens which have been found, without the certainty that the rest of the colonnade was done with the same kind of column. It also has to be specified that the two large capitals of complex A were too damaged on their discovery to allow a reconstruction: it was different capitals, from the church of Kursi in Galilee that were used as a model.

Choice pieces for the future room of the “Holy Sepulchre”

The archaeological section of the Terra Sancta Museum is due to have a floor devoted to the different shrines in the custody of the Franciscans. The queen of all the holy place, the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre will naturally have a room dedicated to it and which will house these ruins. However, considering their impressive dimensions and above all their weight (several tons), their moving to the shrine of the Flagellation is a major challenge requiring a great deal of preparatory work.

1. Clearing and cleaning the pieces

Moved to the shrine of Gethsemane, these ruins were installed in the garden of the Hermitage where they have, until today, peacefully acted as ornaments. At the time of their transport to be kept at the Flagellation, it was necessary to free their base from the terraces on which they were resting (fig. 12), to realize in full their dimensions and do a 3D scan (fig. 13).

Then, they had to be cleaned to clear them of organisms (fig. 14, 15), plants in particular, that had developed on their surface. The product used for this operation had been developed for the Vatican Museums, by a professor concerned by the impact of this type of operation on restored pieces, but also on their environment (natural or human). The non-polluting mixture is made up of natural products including oregano.

This last detail is important as Palestine has a local variety of oregano, organum syriacum, very well known locally as it is used for Zaatar, a local spice. As well as being natural, this product offers the advantage that it can be made wholly locally from ingredients available in situ : in short, a local product to restore the local heritage.

2. Identifying cracks and fragility

The most important operation, however, is probably the identification of cracks that have gradually developed in the stone. As the centuries have passed, vibrations, fires and adverse weather have damaged these ruins and their consequences are not always visible or measurable on their surface. Knowing these cracks means being able to act upstream of the transport and installation of these pieces, in order to reduce to a maximum the risk that the operation fragments them even more.

One of the techniques used for this is thermography. Consisting of observing the temperature variations on the surface of the stone, it allows detecting cracks, colder than the surface due to the entrance of air and water, and evaluating its depth.

3. Removing pigments

The last preparatory operation of this visit was removing an extract of the pigment layer which remains on the surface of one of the columns of complex B. Not being linked directly with their conservation, this operation has the aim of analysing these pigments in the laboratory to obtain more precise dating of the work, and perhaps confirmation that it was indeed made a thousand years ago.

Moving these monumental ruins represents one of the most important and impressive sites of the museum in 2022. This action is essential in view of the complete opening of the archaeological section of the Terra Sancta Museum and the future rooms of the Saller wing are being prepared, in parallel, to welcome this historic and archaeological treasure. However, due to the weather conditions which are still unstable as we write this article, this transfer will have to wait until the beginning of May to be done in the best possible conditions. As the saying goes, “Patience is the mother of all virtues….”

(translated from french by Joan Rundo)

[1] From the ancient Greek « ανάσταση » which means resurrection. By extension, this term designates here the circular space, limited by the rotunda, holding the tomb of Christ in the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre.

[2] Architectural order created in ancient Greece, characterized in particular by capitals decorated with leaves of acanthus.

[3] In architecture, the impost is a protruding stone place high in a wall, on a pillar or a column and supporting the base of an arch.

[4] The catholicon is the main church or the main building of an Orthodox Christian monastery. In the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre, several monasteries coexist (Franciscan, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Ethiopian, Coptic and Syriac Orthodox). The catholicon is the church belonging to the Greek Orthodox, situated in the centre of the Basilica and the entrance of which faces Christ’s Tomb.

[5] According to Saint Jerome, two temples had been erected. A temple dedicated to Jupiter on the tomb of Christ, another dedicated to Venus on the Calvary.

.