The restoration of the pharmacy of St Saviour, an activity in the heart of the museum

Previously on display in the old museum of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum (SBF), in the convent of the Flagellation in Jerusalem, the pharmacy was withdrawn from display in 2013 when work first started on the project of the TerraSancta Museum, the new museum of the Custody of the Holy Land on Christian history. Now belonging to the future historical section which should open in 2023, the pharmacy will be on display, this time in the convent of St Saviour, thus returning to its place of origin, and will be in a completely new setting as close as possible to its historical layout.

Before they can go on display, however, an important stage in the preservation of these objects is taking place: their restoration.

Of what does the restoration and particularly that of the pharmacy of St Saviour consist? And why is it necessary?

Let’s go back to this central activity of museums in three questions.

1.What are the main stages of restoration?

Before any work at all, the object has to be thoroughly examined, a restorer tells us. This preliminary phase of observation is crucial as it is the one that is going to determine the whole work of restoration. The object is examined in its general state to identify any deterioration (shards, cracks, missing parts, but also fading of colour or further repairs) but also in details to learn about its composition. It is at this stage that the materials and the different products tested on the samples taken can be analysed to ensure the piece’s good reaction to the future work. Of course, depending on the object to be restored, this can be complicated to varying degrees, we are told; the pigments used in painting, for example, are far more sensitive to exogenous agents. For archaeological material or pottery, the production materials are generally fairly similar and experience allows very quickly knowing the most suitable products.

For all that, for the jars of the St Saviour pharmacy, there is sometimes the difficulty of having a whole piece missing, at the level of their structure (a handle has been broken, for example) or their decoration. The issue is then to reconstruct this part, respecting to the maximum the general profile of the object, its curves, its colours, the effects of the textures etc. which at times can be a real challenge. In the absence of the models or moulds of origin, the restorer then has to recreate this missing part from all the sources at their disposal (academic publications, archives, other original pieces if they exist, etc.). In the case of the St Saviour pharmacy, the important number of jars preserved has allowed by comparison establishing quite quickly a satisfactory model. However, several attempts are always necessary in order to produce several samples which are then assessed and selected in agreement with the scientific team of the museum.

Lastly, a final discussion at this stage also aims to analyse the display environment. Just as important, this work aims, this time, to anticipate the deterioration that the object will be subject to after its restoration in order to be able to prevent future damage. For example, will the object be exhibited inside or outside and will it come into contact with the wind or the rain? Will it be protected against manipulation? Or will it be subject to the UV rays of the sun or the flashes of visitors’ cameras?

It is after this long stage of preparation that restoration proper can begin.

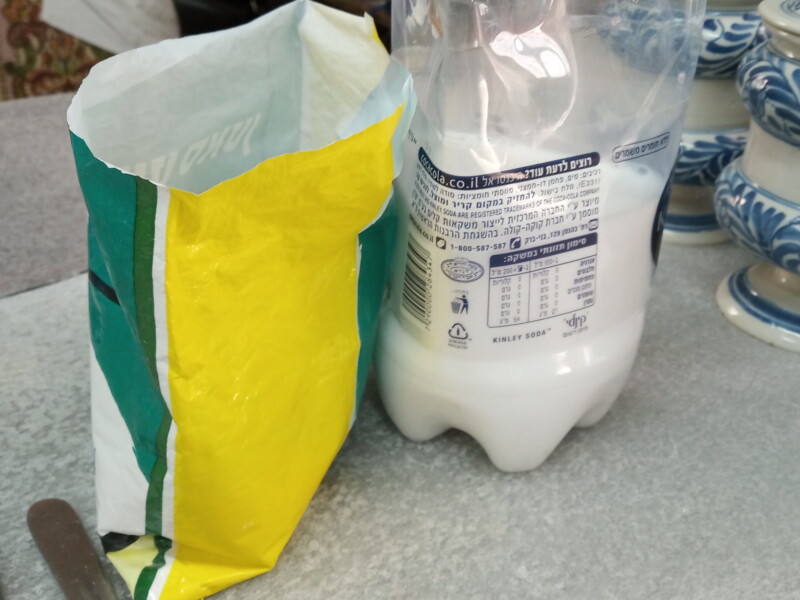

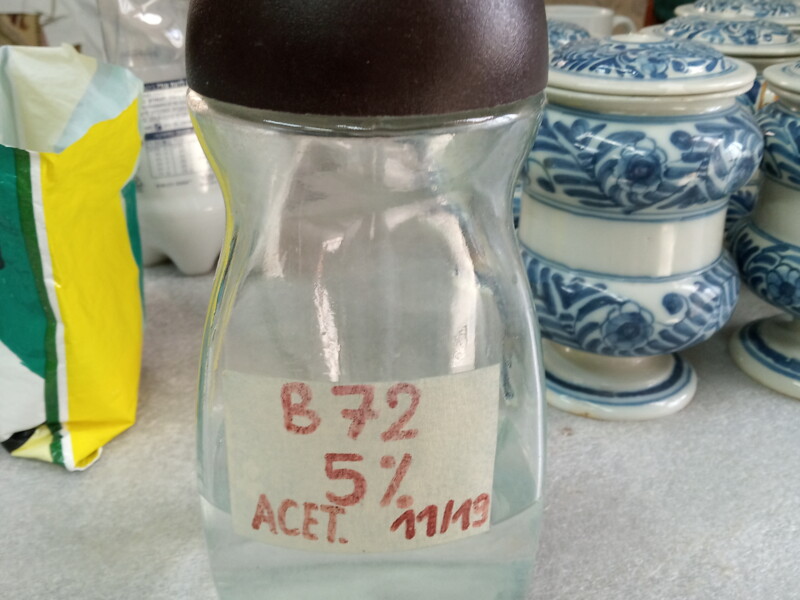

One material in particular is used in the case of the pharmacy: a plaster obtained by mixing gypsum with a solution of pure acrylic dispersion.

Because it is as close as possible to the material of the structure of the jars by its composition and its white colour, plaster is used for all the cases of splinters, cracks and missing parts: it effectively replaces the clay-based paste and is used as a filler. In addition, thanks to the acrylic dispersion, plaster is more solid and its adhesion to the original structure is reinforced.

Then, for the parts requiring a reproduction of the painted decoration, a layer of pigment based on high quality gouache is applied. Lastly, an acrylic resin covers everything. This last coat allows protecting everything from the outer environment, including ultra-violet rays and flashes, and reproducing the shiny effect of the original glaze.

2. Isn’t there a risk of masking the history of the objects in restoring them?

Indeed, if the interest of displaying objects comes from the history they convey, shouldn’t we leave them as they have come down to us? The original context of each piece is often the main element of the discourse. Its history since this context, use and therefore deterioration are necessarily an important part of it and it can thus appear logical to leave them for everyone to know.

The pertinence of restoration is hence always questioned (except perhaps in the case where the intactness of the object is really threatened) and the debate has not yet been settled one way or the other between the supporters of complete and invisible restoration or minimal and apparent restoration.

It is clear that the museographic project plays an important part in the decision-making process (is it to be exhibited in a group, for itself or as an accessory in a larger grouping, for its precise context of origin or in a reconstitution?) The decisions on restoration are also made case by case, even though since the Venice Charter of 1964 the line of conduct tends in all cases to act in the direction of being closer to the established original state of each object (to fight against all arbitrary restoration, more common in the 19th century).

Concerning the pharmacy of St Saviour, the decision was made to approach as far as possible its state shown by the archives [1]. The interest of restoration is then also justified in the wish to offer an immersive experience in a recreated pharmacy, to the contrary of the typological presentation which characterized the old museum of the SBF at the convent of the Flagellation. A certain unity is therefore necessary, especially as the presentation of incomplete majolica jars is of little scientific interest.

Example of a former restoration made by the friars

However, although they aim to be discreet, these restorations will nevertheless be visible. Adopting an intermediate position, the museographic project of this pharmacy includes, in parallel with a faithful and complete reconstitution, being able to see the different work that has been done individually on these jars in time, from the first repairs of the friars to the contemporary professional restoration.

3.Lastly, does the restoration only have an impact on the object?

The priority of any restoration is of course the object, whether it is about restoring its original shape, its splendour or preserving it from future deterioration. However, it can easily be understood from our last observations that its impact is felt much more widely than on the sole object of work. Because restoration is directly on the piece, whether it is seen or not, it acts on what we perceive of the work. As a consequence, it is the experience that the visitor has of the object that is also shaped by the restoration. Becoming aware of this is to realize that a museum is not a neutral place of exhibition and equally to what extent restoration is an activity of the museum project in its own right.

Besides, it is in this sense, that of a transparency of activities and of the museum project, that museums have been gradually progressing over the past twenty years or so, showing the behind-the-scenes for all to see. It has to be understood though that this desire for transparency is also a way of communicating more freely both on its activity and on its scientific choices and decisions of museum policy, and publicly defending these (with their publics as well as their benefactors).

We often approach a museum only through the visible part of its iceberg, in other words its exhibition spaces. The reality of its activity is always slightly more complex. For all that, looking a little closer, as will be the case for the future display of the pharmacy of St Saviour, each person can learn a lot about the work and the decisions these exhibitions stem from.

Because it is at the crossroads of several questions (both technical and scientific or political), restoration is an essential operation in museum activities. But it is revealed at the same time as completely unique, since, more than any other, it is a bridge between scientific disciplines which at first sight are very distant: archaeology, history and history of art on the one hand, physics and chemistry on the other.

> Click here to know more about the history of the pharmacy of Saint-Savior

> Click here to know more about the collection of the pharmacy of Saint-Savior

(Translated from french by Joan Rundo)

[1] The pharmacy was founded in the 14th century and operated until 1917. During all these years its form and composition have changed a lot. The oldest visual archives available to the Custody of the Holy Land date back, however, only to the end of the 19th century. It is therefore this state which has been retained especially as it is the closest to its last disposition.